ANNETTE HUR

Interview published July 28, 2021

Annette Hur 허선아 was born in South Korea and currently lives and works in Brooklyn. Recent exhibitions include solo/group exhibitions at Hesse Flatow, Assembly Room, Wallach gallery, Gavin Brown Enterprise, RegularNormal, Urban Zen, Times Square Space, 33 Orchard gallery in New York; Fairleigh Dickenson University in New Jersey; Devening Projects, Heaven Gallery, Chicago Artists Coalition, Boundary in Chicago. Hur’s work was featured in New American Paintings issues 134 & 135, Friend of The Artist Volume 11, Create! Magazine issue 13, the online art publications: 60 minute art critic, NewCity Art, ADF Magazine, Bad at Sports and Third Coast Review, the online news: Naeil News, The preview, Sisa today. Hur was a nominee for Rema Hort Mann Grant in 2019, a resident of BOLT Residency at Chicago Artists Coalition in 2016-2017. Hur holds a BA from Ewha Women's University(2008), BFA(2015) from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and MFA(2019) from Columbia University.

Hi Annette! Thanks for joining me for Mint Tea. To begin, what’s your favorite tea? If you don’t drink tea, what kind of coffee or drink do you enjoy the most?

I drink lemon ginger tea these days, quite religiously. It started with the pandemic, I thought that it would really help my immune system – it didn't, but I think it's more like a mental thing at this point than a health thing. I try to stick with non-caffeinated tea, and that's my choice. It gives me a nice zing from the ginger, but also the lemon part calms me down. I like coffee too, but I try to stay away from caffeine as much as possible, so I don't drink more than one cup a day.

Could you tell me about your background and your practice?

Sure. I was born and raised in South Korea, and I was an educator and a children's book researcher, developing curriculums for young children and stuff like that for about six or seven years. I started painting seriously in 2012. Basically, I started over, I decided to shift my career completely in my late 20s, to become an artist. And I moved to the US in 2013, and since then, I've been just making art, mostly painting

What projects are you working on right now?

Large-scale abstract paintings. These days, I've been thinking a lot – I had a recent solo at Hesse Flatow Gallery, and working towards that show, I really thought about what traumatic time means to you individually. I've been thinking a lot about those experiences that are unresolved, because once you have trauma, it just kind of perpetually lives with you. And so how those moments reside in our body and mind. These recent paintings engaged the kind of internal dialogue within yourself, the body's desire to reveal and unfold those perpetual stories of a body that went through traumas that you still deal with on a daily basis. If you look at my paintings, the image comes with myriads of broken parts and flavors of colors and it’s kind of chaotic. This unsettling or disappointing drama is my kind of literal representation of the leftover chaos from those initial traumas, and I'm trying to create this process slash battlefield, how it feels to live with trauma. It requires a way of painting that shows that transitional time – very precarious, because you just never know when those moments would attack you at any time in your life.

I also make textile collages, but I'm staying away from those a little bit just because I want to have a really solid body of paintings, first, until I feel really good about letting that narrative go. I mean, I might not let go, but as long as I can, I want to stick with it, and like accomplish a body of those paintings. So I've been working in the same dialect since last year.

Annette Hur, “Mother,” 2020, oil on canvas, 82 x 78 in.

Annette Hur, Installation View of “Willful Unknowing” at Hesse Flatow, 2021

I am the most familiar with your paintings and silk collages. Can you talk about how and why you choose to work with the media that you do?

Painting is my favorite medium, not to just work with but also to look at, since I was little. I think I'm just very fascinated by the fact that it's so easy for humans to be immersed in this make-believe space that is created by a human being, it's like a flat, 2-D surface, but you just go into that world without any verbal or written language. And those images are not photographed or documented from the real world, but it's filtered through a human body, like any drawing and any painting. What that does to the anonymous viewer, it's just really powerful and beautiful to me. So I stick with painting in that sense, but oil paint, among all those different types of paint, I stick with because it feels like there's no clear separation between me and the medium, and even the canvas surface. Like the infinite fluidity of it, or the possibility of what it can do as paint to create imagery, it surprises me every time I paint. That gives me this thrill that I need while I create something. And it's also very forgiving, so I like that part.

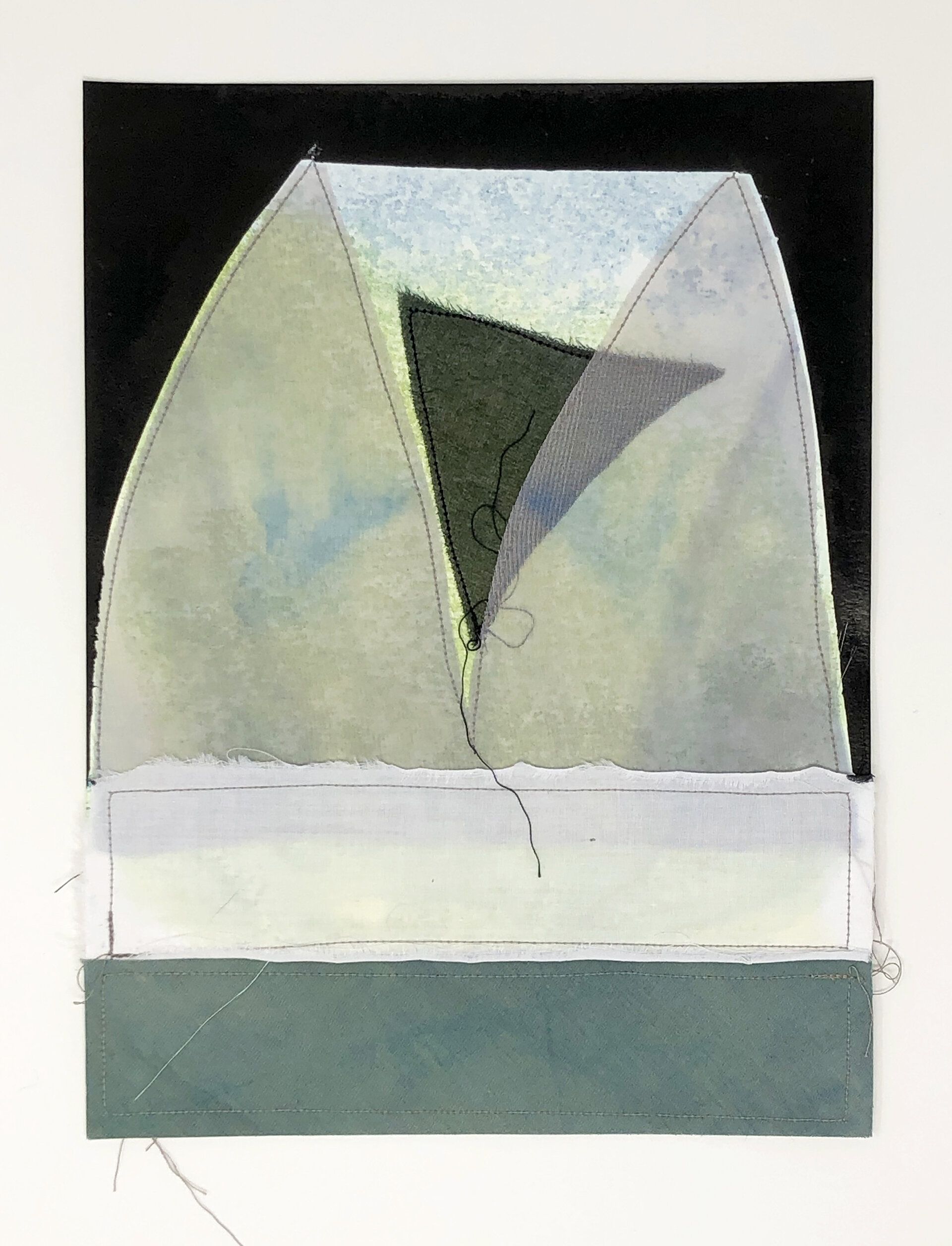

Silk came in kind of late in my practice, in 2018. While I was in grad school, I was trying to deal with my own Korean silk dresses that I owned. I bought them for specific reasons, but they were no longer useful on any sort of occasion. I was never going to wear them because of their own history and meaning and memories, so I wanted to kind of re-form them in something that is not about those but something really new, instead of just dumping in the trash bin. It felt like a medium that made sense to me to work with, along with my painting, with all those colors, transparency, translucency – the material gives me like a completely different approach from painting. It's more intricate and it's very intimate, but it's also less flexible, and very time consuming. I felt like it's the right thing to do at that time, and I continued doing it because I really enjoyed the process of reconstructing the cultural material and how it's related to my identity, specifically, more so than oil paint, and just making it into some artifacts of a different culture and time.

Annette Hur, Installation View of “Willful Unknowing” at Hesse Flatow, 2021

Your paintings are very emotional. What is your creative process like? Do you start the painting with a certain emotion in mind and explore that as you go or do you have a specific image in mind from the beginning that you build on?

I hear that a lot about being emotional. I mean, I agree – I deal with traumas, how can those be not emotional? My recent paintings have stories that exist solely on an emotional level, rather than a literal way, but it still feels more real than anything that's in reality because it lives in your body. So it is inevitable that my images appear really expressive, like, wanting to share the process of figuring out the balance out of a broken beam or something like that. So I agree, they are kind of emotional paintings. And when I start painting, I have this specific story in my head, and I have also an image that is made up by me. I don't have a photo reference, or a full sketch of what I'm going to do, I just have like a basic idea of, “Okay, I'm going to use these references or this kind of symbol, and this put in this composition and I'm gonna achieve this level of emotions.” And then I go into it, so I just do a rough neutral color sketch, and then I usually start with multiple layers of underpainting, and then everything else just comes really intuitively.

You talked about how you think about trauma a lot when you paint. Do you consider painting a way of healing, or is it a process of contemplating the trauma?

When I decide to make a painting about a certain trauma, it's not like a literal 100% transfer from here to there on canvas and I'm done with a trauma, like, I'm healed. That's never going to happen. But, because it's really complex, one trauma is not just about like the loss of somebody very significant, or a sexual trauma in childhood. You can put it in words, but the feeling and the pain, the process you have to deal with in your life is a long-term game, and it's very complex. It's really hard to put in a few words what it feels like, and your body also doesn't know how to process it. Sometimes you have nightmares. Sometimes you have panic attacks. I feel like it's a way for me to look at that incident or that unfair time that I had, outside of my body. Like, I want to look at it and see if I can put it in some other form, if I can visualize it. Because it's hard to put in a few words, what if I visualize it in a way that more people can – not necessarily sympathize with me, I don't really like to sympathize, because I'm not asking for sympathy – I want the painting to be really open in an emotional way, and an intelligent way. So the people, the viewers, and the painting can meet somewhere depending on your own culture, depending on your own lifestyle, traumas, you know, we all have those. And for me, personally, it's just a way to look at it outside of my body and give this story another space to live, and maybe, partially move on. So I guess it is a type of healing. Even if it’s a teeny tiny bit. I feel less burdened once I make a painting about that story.

Annette Hur, “Willful Unknowing,” 2020, oil on canvas, 82 x 78 in.

Annette Hur, “Black Cloud,” 2020, oil on canvas, 82 x 78 in.

Is it important to you that the viewers feel a similar emotion as you when they look at your paintings? For example, sometimes I paint a scene based on sadness and isolation, and some viewers will think only that it’s beautiful.

I think it depends. Would I really want to hear, “Oh your, your painting looks just happy,” or “Your painting looks super cheerful?” Because there's definitely a joy of painting in my paintings, like I love painting itself so much. There's definitely love with the medium, like I'm enjoying my painting, that joy is there. But the imagery and the palette that I choose is very specific. So I would do my best to reach the level of emotion. For example, one of my paintings is called “Our Collective Bodies.” It's about collective trauma, as women, as minorities, and this thing that we're all going through together, and they're all kind of falling apart, but they're also standing pretty strong, trying to go up all together, keeping their own form and strength and everything. But they do it because they are going through a lot of those unfair moments in their life and threats around their bodies. It's not necessarily, “Oh, we're sad and depressed because we're in the situation” or, “Hey, we're dying, look at me.” It's not that, it's more like, “This is where we are at right now. This is what it is, but we're still lifting to this territory of finding our position.” It's complicated emotions that I can't even put in a few words. As long as the imagery is read by viewers, okay, this is this feels like a collective effort, this feels like there's some camaraderie going on.

I'm also always welcome to have more conversation about what other people think about my paintings, how they feel about each individual painting, because I shift and jump from one image to another very quickly. I have this thing, I can't paint the same image twice, which I think is a curse. I torture myself, but I don't know how to paint the same thing over and over again. I admire those people who have those beautiful obsessions with certain imagery, and they do it over and over again, and they evolve through time. I just haven't developed that yet. I hope it comes sometime.

What kind of emotions do you channel while you paint?

All sorts, I would say. As I said, I'm really not good at putting emotions in words. That is probably why I paint this way. I think I'm trying to reach the complexity of it, I'm trying to say that it's not that simple. It's not that simple to live with and process those emotions. And it's not necessarily like, anything wrong, or like something that's you should be depressed about, it's just part of life, and I embrace it, and this is how we embrace it. This is how we deal with it. This is how I once felt, this is what I saw in my dreams. I'm just kind of sharing, because I believe we all have that. Because it's not about me, at all. I start with my own stories, because that's genuinely real to me, but I see so many people, I hear so many unfathomable stories from my friends, my family, relatives, on news, and just I think as I get older, I think about how we cope with all of those things and still live. It's not simple, and I think I'm trying to get that complexity. But just showing it, I’m not making anything more complicated than it would be. Just, complex and immediate.

Annette Hur, "Untitled (Camo)," 2O19, Korean silk and mixed media, 14.5 x 1O.5 in.

Annette Hur, "Untitled (Green and Black)," 2O2O, Korean silk and watercolor on paper, 12 x 9 in.

I really love your silk collages. The colors of the silk and the way they are gently folded remind me of hanbok. How did you start working with silk? Do you dye the silk yourself?

First of all, I love hanbok. Even looking at them, I'm just in awe. How do you do this? I would love to get new ones because I've destroyed most of my previous ones because I didn’t want to wear them, not because they look horrible, but because of their history. But I love the design, I love the material, I know there is like a really deep conversation that we can have in terms of what it means, between different types of hanbok, different ways to wear it. It defines people, it’s horrible, it subjugates women, and everything about it in the past wasn't necessarily beautiful and nice, but just aesthetically, they're just so beautiful and well crafted. I started with my own dresses, as I said, and I chopped them apart, cut them apart and tried to make something out of it, something more individual and intimate. After using all my clothes, I started just collecting more silk, mostly from Korea, and I started also using other materials, like debris, leftovers from a clothing market, like a bra strap or an insert like shoulder pads and stuff that they were going to discard, I would collect them and then try to combine all those. Because what I'm trying to do is making them into some kind of transitional time, like in my painting. I want that to happen in my Korean textile in a different form. The way I could do it with those less flexible materials is to collect different things, different times and cultures, and then make something new out of it. I don't necessarily dye the silk on my own. I tried, and it works, but it's a lot of work. It's too hard. I do a lot of staining though. I like staining with acrylic watercolor ink. I don't consider that the same as dyeing. I would like to try dyeing more when I get more white silk from Korea.

Annette Hur, “Moth Red on Red 00.01 (dyptich),” 2O2O, Korean silk and watercolor on fabric 16 x 13 in. each

Annette Hur, “Moth Trace 01,” 2020, watercolor and acrylic on fabric, 34.5 x 31 in.

Annette Hur, “Moth Bed sheet 00,” 2020, fabric, ink, and acrylic on bed sheet, 57.5 x 66 in.

Can you talk about any imagery or symbols that you like to work with?

On my canvas, most of the imagery is very metaphorical. It's not like a literal translation from the story. I'm borrowing the images of insects, animals, flora, things that are in nature because I think it delves into this very expressive power of a simple apparatus as a body. You know, we think about those insects and animals and we feel they are more intuitive, they're instinct-based rather than brain-based. They're about survival, they're about vulnerability, they have short lifespans, and it's just really about survival, if you look close into nature. So I love borrowing those ideas, that immediacy and survival mechanism. I guess it's like a sneaky way to get a little closer to this violent experience. Because I have sometimes almost wanted to remove my head while I paint – like I want this to be fully, very experiential, in an essential way. So I love having those forms.

How do you think the size of the canvas that you work on affects your work?

I prefer working bigger, to smaller – actually, at least bigger than my body size. It gives me a chance to not see the full picture at the same time while I paint one area. I can really focus in what the paint can do or what the paint at the moment creates in terms of the relationship between colors, between forms, how they mingle and each section creates individual relationships. It also creates complexity, but also it kind of commands time. For me, with smaller scale paintings, because I can look at the full picture at once, my head interrupts, I can't really focus on what that moment does. I would rather like be bothered by how the part that I'm working on now contributes to the whole picture. And it makes sense for my paintings to be a little bigger, because it's about bodily experience. I think in that way, it's more direct, like it's your bodyscape as well. It's more direct and accessible in terms of the subject matter to the viewers.

What is your favorite color? Does it find its way into your artworks?

I think my favorite color is very deep blue, like phthalo blue. I don't necessarily believe that affects my choice of colors in terms of painting. My palate is really intuitive. It tunes into that intensity of the emotions involved and the urgency of finding the balance of that reality in the painting. Each color is super reactive to the color that was right before. Also I try to adapt the colors from nature, if I'm referencing some of those symbols. So I would say it's a series of very visceral decisions for either concealment or disruption of the forms. Like trying to reconfigure the broken thing or body, or trying to find a little bit of control over the things that you couldn't be in the past, or in the initial promise.

Is there a new medium that you would like to try or to work in more?

It's not new, but drawing. I'm a little bit ashamed how few drawings I make, in terms of my creative practice, because when I walk into my studio, which is my living room at the moment, I still just grab a brush and just go at it. I don't know why I'm so aggressive, like, paint, paint, paint. But I want to be more contemplative, to sit down and doodle and draw. Because I know the power of drawing, I truly believe in it, but I'm not like an avid drawer that I want to be. So I'm going to try that really hard this year. I would stick with graphite, then maybe charcoal. I love those two, but probably graphite first and then slowly into charcoal. I teach drawing, but I don’t draw enough. It’s my personal secret that I’m sharing right now.

Annette Hur, “Without Looking,” 2020, oil on canvas, 82 x 78 in.

Where are you located now? Do you think Brooklyn influences your practice? How was your art different in Seoul, Chicago and Brooklyn?

I am in Gowanus, in Brooklyn. It's in between an industrial and residential neighborhood. I love being here. It's close to everything, and I have my home studio in my living room that I share with my roommates. I love Chicago – the time I was in Chicago from summer 2013 to 2017 was such a blessing. I can't complain anything about it, and I cherish that until this moment, I met so many great artists and mentors and art supporters or enthusiasts. It is definitely a smaller community compared to New York, and that actually was very helpful for me to make this quite smooth transition from being a non-artist in Korea and becoming an artist in the US, because of the wonderful, supportive people I met. The community is great there. I think what I love about New York and Brooklyn is the diversity. Not necessarily the size of it. I mean, it is exhilarating, everything is here, everybody's here, but it's also expensive. It's like a constant struggle, money comes in your head all the time because you have to pay rent, and it really bothers me a lot in terms of making the studio, like how many part time jobs do I have?

But what's great about this place is it constantly makes you think a little harder than you would in any other place, especially when you're a non-white American, because you have to constantly think about where you stand, like where your body belongs in this society, like, do I belong here? What does it mean to be a first generation Korean American artist, here in New York, it's like a constant battle to either assimilate or stand alone. I am part of this community called Asianish, and we have a lot of conversations about those issues, especially at this time. And we – in these similar minority communities, whether you're Asian or brown, Black – do not take anything for granted. Whether it shows in your art or not, we are always working through that in our creative practice. I think that gives me a lot of strength to create more work, even though it's not directly addressing the issue that I'm dealing with, but it's all related. A lot of traumas come from the culture that I'm surrounded by, as an individual, what I go through, as a woman, as an Asian, starting from my culture that I grew up in, but it only expands here. Yeah, I think that's stressful in some way, but also I think it makes you grow and learn about yourself and other people, and it gives more reason to make more art. So I love being in Brooklyn.

Since we were talking about trauma, that got me thinking about the Korean concept of han, which I identify in my art as a Korean-Canadian living in America. I’m constantly trying to define my narrative, the story of my people and who I am, reinventing myself and keeping some part of myself that is Asian. I wonder if han is something that we are all trying to explore in some way, keeping the culture, and the practice of ancestral storytelling, and keeping the memories alive. Does that resonate for you?

Totally. The works that I made in while I was in grad school were really about that. Specifically about the Asian culture that I grew up in, that harsh, patriarchal society. A lot of women in my mom's generation, my grandmother's generation, they have a lot of han, which is kind of hard to explain in English. It's a complicated emotion, right? I think it's kind of close to “unresolved,” like it's not immediate pain, but it's more unresolved pain that you carry, and you just don't have meetings to resolve it anymore in your life. I guess in that way, it's a little in the same conversation, but for me in my paintings I don't really think so much about it. I used to look at a lot of Korean prostitutes in old times, like Joseon Dynasty. They were so young, they were thirteen, fourteen – so gross. But they were, like, the most beautiful people, most talented. They're musicians, poets, writers, dancers, painters, and everything. And they're the same level as butchers, which was the lowest group in the society. So I thought about it, and I made paintings about them, thinking about subjugated female sexuality in those cultures and everything. But these days, I've kind of moved on to my more personal immediate stories, so I don't know if I actually talk about han anymore, but I know it's still there. It's still there in a lot of people's minds. I don't know how it would go away. Maybe after, like, 30 generations? Yeah, I don't know.

How do you stay connected to your community?

Friends hanging out, social media, phone calls, texts, emails, going to openings, supporting friends’ openings, and just talking. I've also recently started this online curatorial platform called Backyard Ghost. It started literally in my backyard with myself wearing a ghost costume. I was going to keep it anonymous, but people figured it out pretty quickly, so now I don't wear the costume anymore. What I have been working on is curating shows online, and I even curated two shows physically. I have a backyard where people can install their site-specific installations, and my peer artist fellow Bat-Ami Rivlin’s work is installed right now. But I'm very introverted, and I would never have imagined myself doing this kind of thing, outside of my studio. I thought being an artist would be amazing and suit me well, because I can be stuck in my studio and not meet anybody and make paintings, but that's not the case, I learned in Chicago. I wouldn't have thought of doing something like this if it wasn't for the pandemic. I started in the hope of connecting with my peers and other artists, but also just to support each other, especially those underrepresented artists whose work I really admire and enjoy these days.

What’s your favorite tool?

I like cheap brushes. I mean, seriously, I bought so many cheap, big brushes. Like, in the beginning, good brushes are so expensive, and I wanted to paint big, and those were the brushes that I could afford. So that's how I started. I have a few good brushes, but I still use those big cheap brushes a lot and they're my favorites. They're like synthetic, big semi-rounded brushes. As they age, they also give me a different texture, because they get ruined quite a bit. I like to have all sorts of different shapes and sizes of brushes. It's the easiest way to create that complexity in terms of painting language. What they do is all different, individually, so I don't really have like my favorite. But I have a lot of cheap brushes.

What is the space where you do your work?

These days I work from home, so my home is everything for me. I work out here, I paint here, I cook and eat here, I sleep here, I hang out in my backyard. So I've been really investing a lot into create the space of semi-privacy because I have two other roommates. I've got a partition thing going, curtains, and because I'm a messy painter, I did this like vinyl, laid out by myself. I've been trying a lot to create workable, livable, pleasant space in my house, and it's been it's been working out great. Brooklyn in general, I just love being here. It's not too crazy, and even during the pandemic, when people say Manhattan was so empty, Brooklyn never really felt empty.

Do you have any ritual that helps you get into the zone?

Um, not really. I mean, as I said, I come in and grab a brush and just attack my painting most of the time. Just because my studio is at home, in the morning I come downstairs and make some coffee and do some breathing and I let my dog out to the backyard. I like go to get some vitamin D from the sun and do some stretching. That's how I start my day.

When do you know when you are finished with your artwork or a body of work?

I feel I'm done with a painting when I feel the emotional level that I was trying to put in from the beginning. For example, my Korean blue skirt, the silk dress that I had to rip apart. While I was ripping apart the skirt, a lot of those traumas came up and I was crying, but I'm still like creating something, I'm not just destroying it. So that kind of emotional level that I felt – when my painting gives me that zing I decide to let go. So I guess my painting tells me, “Just don't touch me. Stop harassing me.”

Annette Hur, “Breath, Cut or Burnt,” 2020, oil on canvas, 82 x 78 in.

Are there any Korean artists who you especially like?

I like a lot of them. I saw 이우환 Lee Ufan’s show in Chelsea a few years back and I met him in person. I really liked his work. I love 양해규 Yang Haegue’s work as well. She’s really great. I love 김환기 Kim Whanki’s paintings, just to look at them and feel the nostalgia. 백남준 Paik Nam June, also, was pretty genius. I love 김수자 Kimsooja’s Bottari series. The textile works are great. Also 양해규 Yang Haegue’s textile works and those installations are pretty damn amazing. Also, in the beginning when I started painting, I was like, “I don't want to make figurative art,” for some reason and I was looking at a lot of 유영국 Yoo Youngkuk’s abstract, colorful paintings when I didn't know much about like American abstraction. I go back to them on and off, and they're all good inspirations. Yeah.

Who are your favorite practicing artists?

I'm going to stay with painters so I can narrow it down. I would say, I love Cecily Brown’s painting, so much, I just do. Really great inspiration. I always look at Amy Sillman's work, too. And a few years back, I found Lynettte Yiadom-Boakye – her figurative works are my favorite figurative works these days. Because I've been curating shows for the Backyard Ghost thing. I really paid attention to my peers’ work, the artists that I personally know from Chicago and New York, and I'm just gonna give the names. I love Amanda Joy Calobrisi’s work. Her solo show is up at Backyard Ghost right now. She is a great friend of mine from Chicago. And another painter, Biraaj Dodiya. She's also a friend of mine in Chicago, and her recent abstract paintings just really blow my mind.

What gives you the feeling of butterflies in your stomach?

As I get older, honestly, I think it's true, I don't get butterflies. Even if I go on a date or something, I do not get butterflies, and it drives me crazy! I really miss that feeling. But I have to say, Louise Bourgeois’s works still gives me this, I don't know if it's necessarily butterflies, but the excitement of, “Oh, this is why I make art.” I think it's only her art that gives the gut-punching wanting to make art. But yeah, I don't know, butterflies are gone. I hope they come back. I really, really hope.